Schistosomiasis

What is schistosomiasis?

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia or snail fever, is a parasitic disease caused by tiny blood-dwelling worms. It is found in tropical and subtropical regions, namely in Africa, South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and parts of Asia. Infection occurs when individuals, particularly children, come into contact with contaminated water.

Over 200 million people worldwide are infected with over 700 million people living at risk of infection. Over 90% of infected people live in sub-Saharan Africa. It is a disease linked to poverty, with the highest burden suffered by the poorest communities and most neglected, vulnerable people. Infants and children are especially prone to infection due to their less developed immune system.

Schistosomiasis Names:

- Schistosomiasis, Bilharzia, Snail Fever, Blood fluke worm [English]

- Bilharziose, Schistosomiase, [French]

- Kichocho [Kiswahili]

- Sisto [Filipino]

- Tsargiya [Hausa]

- Muozmim [Dangme]

- Esquistossomose [Portuguese]

- ቢልሃርዝያ Bīlihariziya [Amharic]

- Likodzo [Chichewa]

What causes the disease? How does it spread?

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia or snail fever, is a disease caused by small, blood-dwelling parasitic worms. A person becomes infected when they come into contact with freshwater where the parasite lives inside freshwater snails. The parasite larvae leave the freshwater snail and penetrate a person’s skin whilst they are swimming, washing or working in the water. Because the larvae are microscopic, the person is unaware that they have just been infected by a schistosome parasite. There are many different species of schistosomes that infect different animals, but only six infect humans.

The schistosome parasite enters the person’s blood system where it lives and reproduces. Male and female worms mate and can release hundreds of sharp-spined eggs into the person’s blood stream. Some of these eggs, pass from the blood stream into the intestinal or urinary tract (depending on the schistosome species), and they are released into the environment when an infected person defecates or urinates. If the eggs reach freshwater, as they will in areas lacking safe water & sanitation facilities, they hatch into a larval form and infect a particular kind of freshwater snail. Here the parasite may live and develop, releasing thousands of larvae into the water every day. The larvae will look for another person to infect. This is the life cycle of the schistosome parasite. Schistosomiasis transmission cannot occur from person to person without the freshwater snail host and water contact.

Life cycle and Transmission

To understand the disease and how to control/eliminate it we must first understand the parasite's life cycle and how it is transmitted.

When schistosome worms infect people they pierce through the skin into the blood system and travel with the blood to the liver. In the blood system of the liver male and female worms pair up and move to the veins around the intestinal tract or the veins around the urinary tract, depending the species of schistosomes.

The worm pair releases schistosome eggs into the blood system. The eggs pierce through the wall of the intestinal/urinary tract and exit the body through defeacation or urination. They reach fresh water and hatch out into larval stages called miracidia. Miracidia swim through the water to find a specific aquatic snail species. Once they have found the snail species they are looking for they infect them and reproduce asexually, creating thousands of clonal larval stages. These next larval stages are called cercaraie.

Thousands of cercaraie leave the snail and swim in the water searching for their next host - people! When a person enters the water to wash clothes, fish, bathe or play, the cercarie will swim to the person and pierce through their exposed skin. Being microscopic, the person is unaware that they have just been infected by a schistosome worm. The lifecycle continues.

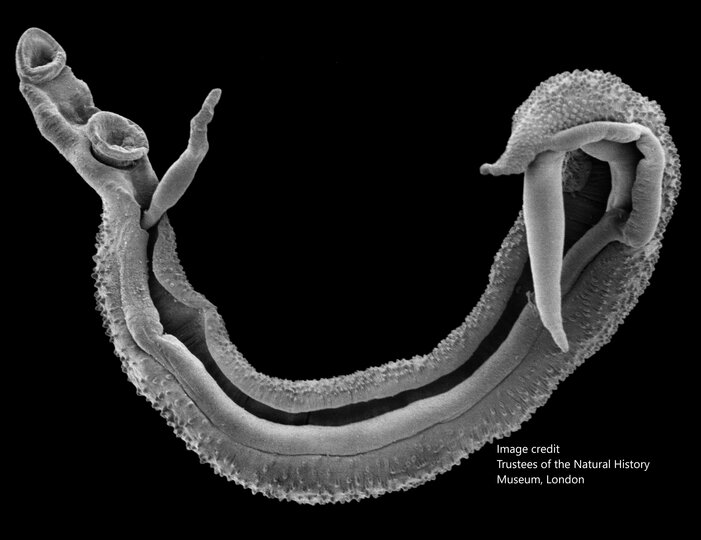

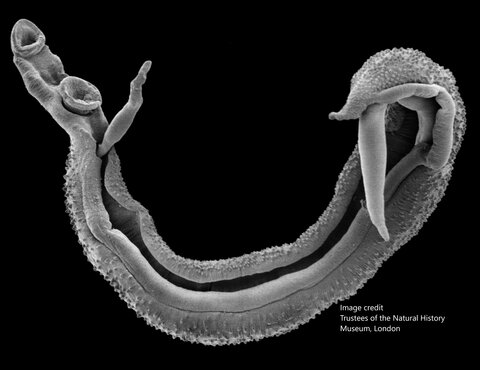

What do schistosomes look like?

This video shows different real life biological stages of the schistosome worm under a microscope. The video was made by our partners at the Natural History Museum and shows the work of the Schistosomiasis Collection at the Natural History Museum (SCAN) team.

The Disease

Infection with the schistosome blood worm causes the disease Schistosomiasis (aka Bilharzia).

The adult worms themselves are not very harmful but the eggs they produce and release into the blood system lead to a lot of damage and are the cause of the disease. Schistosome eggs will either

- Pierce the barrier between the blood system and the intestinal/urinary tract, exiting the body through defaecation/urination, causing pain and cramping. Symptoms of this often include blood in urine, blood in faeces.

- Or the eggs get transported by the blood system into neighbouring organs and tissues, getting trapped there and leading to inflammation and tissue damage

More worm pairs = more eggs = more damage to the organs and the host. This is what causes the chronic and more severe aspects of the disease such as organ damage, bladder cancer, liver fibrosis, genital lesions which progressively get worse in adulthood.

There are two forms of the disease, depending on the species of the infecting schistosome worm:

Intestinal Schistosomiasis

- diarrhoea, bloody stool

- anaemia, stunted growth

- enlarged liver and spleen

- severe damage to the liver leading to liver fibrosis

- portal hypertension

Urogenital schistosomiasis

- blood in urine, painful urination

- anaemia, stunted growth

- damage to the genitals, kidneys and bladder

- bladder cancer

- increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV

Where is the disease found? Why?

Schistosomiasis is both a water-borne, and a vector-borne disease. Water is the medium where transmission occurs. Both people and the freshwater snails (carriers of schistosome worms) become infected in water. It is not surprising that a common characteristic of communities plagued by this disease is the lack of access to safe, clean water. These communities turn to open, natural waterbodies to wash, clean, drink and bathe, increasing the risk of exposure. Areas that lack access to safe, clean water also tend to not have safe, easily accessible and easily maintained sanitation and hygiene infrastructure. This means that waterbodies used by communities and near households are easily contaminated by human waste which gives the schistosome parasite the opportunity to find and infect its preferred freshwater snail (the vector) and multiply. This makes that freshwater body a transmission site, and everyone who comes into contact with it is at risk of getting schistosomiasis.

There are 23 species of schistosome parasitic worms, six infect people, but many others infect domestic animals. The relationship between schistosomes and freshwater snails is intricate and complex. Schistosome parasites will only infect specific species of freshwater snails and not others. The distribution of schistosomiasis is determined by the distribution of these freshwater snails, which prefer warm climates. This is why schistosomiasis is found in tropical and subtropical regions, namely in Africa, South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and parts of Asia.

Of the six species that infect people, three are responsible for the majority of human infections globally:

- Schistosoma haematobium - causes urogenital schistosomiasis and is carried by freshwater snails belonging to the Bulinus genus found in Africa and the Mediterranean.

- Schistosoma mansoni - causes intestinal schistosomiasis is carried by freshwater snails belonging to the Biomphalaria genus found in Africa, South America and the Caribbean.

- Schistosoma japonicum - causes intestinal schistosomiasis and is carried by amphibious snails belonging to the Oncomelania genus found in Asia.

- Another species of regional importance is Schistosoma mekongi which is carried by the freshwater snail Neotricula aperta, found in the Mekong River Basin of Cambodia and Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

|

Disease |

Species |

Geographical Distribution |

Estimated number of infected people |

|

Intestinal schistosomiasis |

Schistosoma mansoni |

Africa, Eastern Mediterranean region, Caribbean islands, Brazil, Venezuela & Suriname |

83 million |

|

Schistosoma japonicum |

China, Indonesia, the Philippines |

1.5 million |

|

|

Schistosoma mekongi |

Cambodia & Laos (very focal though) |

? |

|

|

Schistosoma malayensis? |

Malaysia |

? (rarely in humans) |

|

|

Schistosoma intercalatum |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

? (may no longer have human transmission) |

|

|

Schistosoma guineensis |

Cameroon with some reports of other neighbouring countries although confirmation is needed |

? (very focal to small sites of transmission in Cameroon) |

|

|

Urogenital schistosomiasis |

Schistosoma haematobium |

Africa, Eastern Mediterranean region, Corsica (France), Arabian Peninsula |

114 million |

|

Hybrids/Introgressed forms -S. haematobium-bovis (other introgressed forms under research) |

Africa & Corsica (France) |

The risk of infection is linked to how often people come into contact with infested freshwater. Whilst partial immunity can develop after repeated exposure to the parasite, regular contact with infested freshwater creates a high risk of severe disease at any age. Children who do not have partial immunity are particularly at risk of becoming infected from swimming and playing in the water; bathing and cleaning themselves in the water; or from doing household chores such as washing dishes and collecting water for the household. Children can become infected repeatedly with many schistosome parasites living in their blood system causing anaemia and tissue damage.

Families and communities that rely on fishing in freshwater bodies and on agricultural activities such as rice production are often burdened by schistosomiasis. Exposure to schistosomiasis can be linked to the social context of a community. In communities where fishing and farming are mainly done by males, men and boys are exposed to infections through these occupations. Women and girls are at risk when carrying out household chores such as washing clothes, dishes, collecting water etc.

Snail and schistosome images from the Schistosomiasis Collection at the Natural Histroy Museum of London.